EN PLEIN AIR

the marvelous world of painting outside

You paint, or perhaps you don't, and you would like to start painting outside. Never done it before but somehow you feel the calling. So, you gather your newly bought field easel, your paint brushes and smaller tubes of paint because you prepared yourself well and don’t want to carry extra load, and head of to a local spot of beauty to paint. The weather is awesome, the birds are singing, butterflies are playfully flying around and you feel good. You prepare your mini pallet, have a quick drink of water and are ready to start. Then it hits you, you never done this before. How do you start? You have so many years of experience, you know your stuff, but somehow, sitting there with a warm breeze in your neck, you get stuck.

Recognize this? Trust me, you are not the first…not the only one…and won't be the last one to discover that painting outside is quite different from painting in your studio.

In this article I hope to explain a bit of why this is happening (and you will see that it is rather expected) but more on how you can get the best out of painting outside.

FIRST…a bit of history.

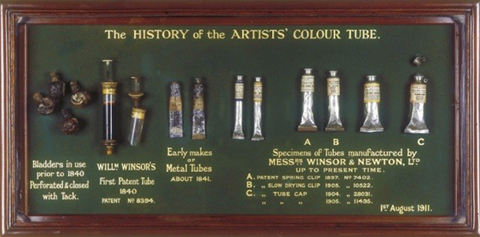

Painting outside, or ‘En Plein Air’ as the French started calling it, is not as old as you might expect. It was all thanks to two things. First of all, the invention of oil paint. Although the use of oil paint was generally considered to start during the 15th century by the Dutch painters, it was much earlier that oil was used to make a paint. Several cave paintings have been found with pigments concealed in walnut oil. Also, during the medieval period, monks were using linseed oil for their book paintings.

Second of all, the invention of a carrier for oil paint, which was done by the American painter John Goffe Rand in 1841. He used pig bladder combined with glass syringes to transport oil paint. Due to his invention, a whole new area of painting arose. It is believed that Pierre-Auguste Renoir who said, “Without tubes of paint, there would have been no Impressionism.”

Makes sense. Impressionist painters became known for their colorful, wild and, as the movement got its name, very impressionistic approach. Many impressionists are recalled for saying that the main goal of painting in this way, was to set a true impression of that specific moment of the day. Using only the time that you could witness the splendor of what you were seeing and trying to catch this with paint on the spot.

Any of you, who have experienced the joy of sitting outside and feel the challenge of catching that specific light, the ever-changing colors, the temperature, and trying to put this within a given time on your canvas, will recognize this.

But what makes it so different from working in a studio? The most obvious is, of course, the fact that you’re not inside but working outside. Although expected, the influences of being outside, the wind, the sun, the noises and naturally the occasional rain…especially when you painting in the Dutch countryside…can have a major effect on how you sit there, with your paint and brushes trying to do your thing. Being in your studio is very different. You are able to adjust pretty much everything to make your working space as pleasant and as constructive to your work, as possible. Try this with that hard-to-reach rocky spot behind a big tree next to a riverbank.

And yet, more and more painters, when discovering the magic of painting outside, get seriously hooked on it.

To work outside, it is best to leave any expectations you have on what to expect, what it will be or what you plan to paint, at home. Why? Because it always will be different.

Once you find a nice spot, accepted all the bugs flying around and ending up in your paint, and mastered to decide what you want to paint, you soon discover the agony of changing light. Trust me, even on a beautiful sunny day with a clear blue sky without a breeze, you will find yourself in an ever-changing light-scape. The painting you start will never be the same as the scenery appears to you at the end of your capturing moment.

AND NOW…some practical advices:

Now a days, the art supply shops seem to know exactly what you need to reach your goal as an artist. If it was only that simple. Absolutely, some wonderful gadgets out there can make your painting-outside-experience much more do-able and pleasant. But don’t make the mistake, and I’m sure you will or already did, to think that expensive, state of the art equipment will ensure great painting. Sorry. It will be much more likely to know that it will be your experience, your persistence and endurance that will ensure some beautiful results.

Nevertheless, some equipment are inevitable to work outside.

To start you will need an easel. And even the need for it is debatable. These days you can buy a lightweight aluminum easel that is easy to carry. Also, small easels from wood are nice and you have the famous box-easels that combines an easel with your paint box. Handy but a bit heavier.

Then the decision is whether you want to stand or sit. For me, standing is great but sitting is greater. I get easy tired in my legs, which makes it uncomfortable to paint. Therefore, a foldable chair is handy.

Take enough rags or pieces of cloth. Yes! please do! I noticed, considering you will have to clean your brushes at home, that it’s so handy to have lots or rags to clean, cover and clean some more, while you out in the fields. I know I do...

Another thing to take in consideration is on what you going to paint on and how you’re planning to transport it. Near my hometown, there is a group of plein-air painters (they go every week no matter the weather) whom use a ingenious system with which they slide several panels in a box. How nifty is that. However, I really advice you to make a system that will work for you to transport you work. I, myself, came up with a sort of cover for the painting. I always prefer to work on linen. I tape the canvas on a fixed size board and have another board, from which the sides are made higher, that is than used as a cover on the painting.

That immediately brings us to another practical tip: the size of your painting.

If you’re planning to go by car and know that you’re going to stay close to your car, the size of your painting is pretty much the size your car can handle. However, if you considering to have a nice stroll before finding a good spot that will embrace every fiber of your being to yell at you that you have to paint this, you might want to think twice before taking up a 1 by 1 meter canvas.

So, in general, small sized panels or canvas are easy to carry, easy to work with and easier to handle. Because, let’s not forget, the idea of ‘en plein air’ is to make and finish a painting on the spot.

So much for practical tips.

NOW…some technical tips and suggestions.

If you ever took the time to examine the impressionist works, you soon will notice that there is a specific use of colors. In fact, certain colors are in a lot of cases not used.

If you walk through the countryside and glans over the trees, the nearby bushes, the hills in the distance and the far away village skyline, as an experienced plein air painter, you will immediately distinguish the different pallet of colors. However, as a typical indoor studio painter you might find yourself wondering how those impressionists came to those, sometimes extreme, choice of colors. To understand this, you have to understand the following. Before the 19th century, during the classical approach in painting, it was general knowledge to paint the exact, or so we thought, color of the object as to emphasize a most convincing resemblance to reality as possible. Due to the fact that till than almost every artist was working in a studio, and natural outdoor daylight was not much available, it is not surprising to see, indeed, almost only colors that we can recognize within our marge of acknowledgeable colors. However, and this was very well understood by the impressionists, when outside, colors seem to change in any given circumstances. Not only by the change of light but also by the influences of atmosphere, distances and humidity. In addition, you will see, if you take some time to sit outdoor looking at a fast landscape, that colors are, indeed, vibrating, and, more important, not as conform as one might think. The impressionist understood this by dividing colors again in warm and cold colors. By using this knowledge in a practical use, you immediately understand why they used so much blue and green for shadows (cold) and bright yellow, orange and red for the more sunny and bright parts (warm) in the painting.

If you take this knowledge with you the next time you embark yourself on an adventure to go out and paint outside, and I encourage you to do so...and I encourage you even more, before you start your painting process, to take some time to just sit and absorb what you see...go beyond the expected colors, beyond what you know you see and beyond what you think you see. Just observe and take it in.

Painting outside, ‘en plein air’ is indeed an adventure. A meeting between you and what you observe, you and what you think is outside you. However, if you let go of these pre-programmed believes and just observe as...yes, we are going to use this word...a child, you will see that colors are indeed more than meets the eye.

Feeling inspired? I hope you do and will go out there and start painting what you see. Let me know.

Also, if in the neighborhood, you can join with one of the plein air workshops I'm giving every summer.

More information (in Dutch though) can be found here: www.schildercursusarnhem.nl